Micronutrient research presents a labyrinth of conflicting studies, methodological challenges, and population-specific variations that can leave even seasoned health professionals questioning their dietary recommendations.

🔬 The Complexity Behind Micronutrient Science

Understanding optimal micronutrient intake requires navigating through decades of research that often contradicts itself. Unlike macronutrients, which we consume in gram quantities, micronutrients operate at milligram or microgram levels, making accurate measurement extraordinarily difficult. The human body’s intricate relationship with vitamins and minerals involves absorption rates, bioavailability, genetic variations, and complex interactions that transform simple nutritional questions into multifaceted scientific puzzles.

Research methodology in micronutrient studies varies dramatically across institutions, time periods, and populations. Observational studies suggest correlations that randomized controlled trials fail to confirm. Laboratory findings in isolated cell cultures don’t always translate to living organisms. Animal models provide insights but can’t perfectly replicate human physiology. These methodological limitations create uncertainty that permeates even well-established nutritional guidelines.

📊 Sources of Bias in Nutritional Research

Publication bias represents one of the most pervasive problems in micronutrient research. Studies showing positive effects of supplementation are more likely to be published than those showing null results. This creates a skewed literature where the evidence base appears stronger than reality warrants. Researchers, journals, and funding bodies all contribute to this asymmetry, making comprehensive meta-analyses challenging.

Industry funding introduces another layer of complexity. While not all industry-sponsored research is biased, financial conflicts of interest can influence study design, outcome selection, data interpretation, and publication decisions. Supplement manufacturers have vested interests in positive findings, while pharmaceutical companies may benefit from demonstrating that dietary approaches are insufficient without their products.

Population Selection and Generalizability

Most micronutrient studies focus on specific populations that may not represent your personal circumstances. Research conducted on elderly nursing home residents in Scandinavia may not apply to young adults in tropical climates. Studies examining deficiency states in developing nations provide different insights than those investigating optimization in well-nourished populations. Gender, age, genetic background, existing health conditions, and lifestyle factors all modify micronutrient requirements in ways that broad guidelines cannot capture.

The healthy user bias further complicates observational studies. People who take supplements often engage in other health-promoting behaviors—exercising regularly, avoiding smoking, maintaining healthy weights, and seeking preventive care. When these individuals show better health outcomes, attributing benefits specifically to micronutrient supplementation becomes nearly impossible without carefully controlled interventions.

🧬 Bioavailability: The Hidden Variable

Knowing the micronutrient content of food or supplements tells only part of the story. Bioavailability—the proportion actually absorbed and utilized by your body—varies enormously based on multiple factors. Iron from red meat (heme iron) is absorbed far more efficiently than iron from plant sources (non-heme iron). Vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol) raises blood levels more effectively than vitamin D₂ (ergocalciferol). These distinctions rarely make headlines but profoundly impact nutritional adequacy.

Food matrices influence absorption in complex ways. Consuming fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) with dietary fat enhances absorption. Phytates in grains and legumes can bind minerals like zinc and iron, reducing their availability. Vitamin C enhances iron absorption while calcium inhibits it. Cooking methods, food combinations, gut health, and even the time of day you consume nutrients all affect bioavailability in ways that standard nutritional databases cannot capture.

Individual Genetic Variations

Genetic polymorphisms create substantial individual differences in micronutrient metabolism. The MTHFR gene variations affect folate metabolism, potentially increasing requirements for certain individuals. Variations in vitamin D receptor genes influence how effectively your body responds to vitamin D. These genetic differences mean that population-level recommendations may be suboptimal for significant minorities—or even majorities—of certain ethnic groups.

Nutrigenomics, the study of gene-nutrient interactions, promises personalized nutrition but currently delivers more questions than answers. While genetic testing companies offer micronutrient recommendations based on DNA analysis, the science remains preliminary. Most genetic variants have modest effects, and environmental factors often overwhelm genetic predispositions. Treating genetic test results as definitive guidance would be premature given current understanding.

⚖️ Interpreting Conflicting Study Results

When confronted with contradictory research findings, several strategies can help you navigate toward reasonable conclusions. First, consider study hierarchy: randomized controlled trials generally provide stronger evidence than observational studies, though both have limitations. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses synthesizing multiple studies offer broader perspectives than individual papers, though they inherit the biases of included studies.

Examine the outcomes measured in different studies. Research showing that vitamin E supplementation doesn’t reduce heart attack risk doesn’t necessarily contradict studies finding improved endothelial function. Different outcomes may respond differently to the same intervention. Similarly, studies examining deficiency correction provide different insights than those investigating supplementation beyond adequacy.

Dose-Response Relationships Matter

Many micronutrients exhibit U-shaped or J-shaped dose-response curves where both deficiency and excess cause problems. Selenium exemplifies this pattern—inadequate intake impairs immune function and thyroid health, while excessive intake causes toxicity. The optimal range may be relatively narrow, and population-average recommendations may not suit individuals at either end of the requirement spectrum.

Study durations also influence outcomes. Short-term supplementation trials may show effects on biomarkers that don’t translate to long-term health improvements. Conversely, some micronutrient benefits require years to manifest, making them difficult to capture in typical research timeframes. Vitamin D’s potential effects on cancer risk, for instance, might require decades to detect definitively.

🍎 Food Versus Supplements: A False Dichotomy?

The debate between obtaining micronutrients from food versus supplements often generates more heat than light. Whole foods provide nutrients in complex matrices alongside fiber, phytochemicals, and other beneficial compounds that supplements cannot replicate. Food-based nutrition also reduces risks of excessive intake that concentrated supplements pose.

However, supplements serve legitimate purposes in specific contexts. Vitamin B₁₂ supplementation is essential for vegans since plant foods contain virtually none of this critical nutrient. Folate supplementation during pregnancy reduces neural tube defect risks. Vitamin D supplementation benefits populations with limited sun exposure. Dismissing all supplementation as unnecessary ignores these evidence-based applications.

Fortification Adds Another Layer

Food fortification programs have dramatically reduced certain deficiency diseases—iodized salt virtually eliminated goiter in developed nations, while folate fortification reduced neural tube defects. Yet fortification also creates uncertainty about baseline nutrient status. When calculating your micronutrient intake, should you account for fortified breakfast cereals, enriched flour products, and fortified plant milks? These additions make dietary assessment more complex while potentially masking inadequacies in whole food consumption.

Geographic variations in fortification policies mean that identical dietary patterns yield different micronutrient intakes across regions. North American flour contains added folic acid while European flour generally doesn’t. These policy differences make international research comparisons challenging and dietary recommendations context-dependent.

📱 Technology and Tracking Limitations

Numerous applications promise to track your micronutrient intake and identify deficiencies. While these tools provide useful approximations, they inherit all the uncertainties discussed throughout this article. Nutritional databases contain average values that may not reflect the specific foods you consume. A tomato’s vitamin C content varies with variety, growing conditions, ripeness at harvest, storage duration, and preparation method—none of which your tracking app accounts for.

Self-reported dietary intake notoriously suffers from recall bias and social desirability bias. People underreport foods perceived as unhealthy and overreport nutritious options. Portion size estimation introduces additional error. While food tracking increases awareness and can identify obvious inadequacies, the precision these apps display (showing intake to the nearest microgram) implies a false certainty that the underlying data cannot support.

🩸 Biomarker Testing: Promises and Pitfalls

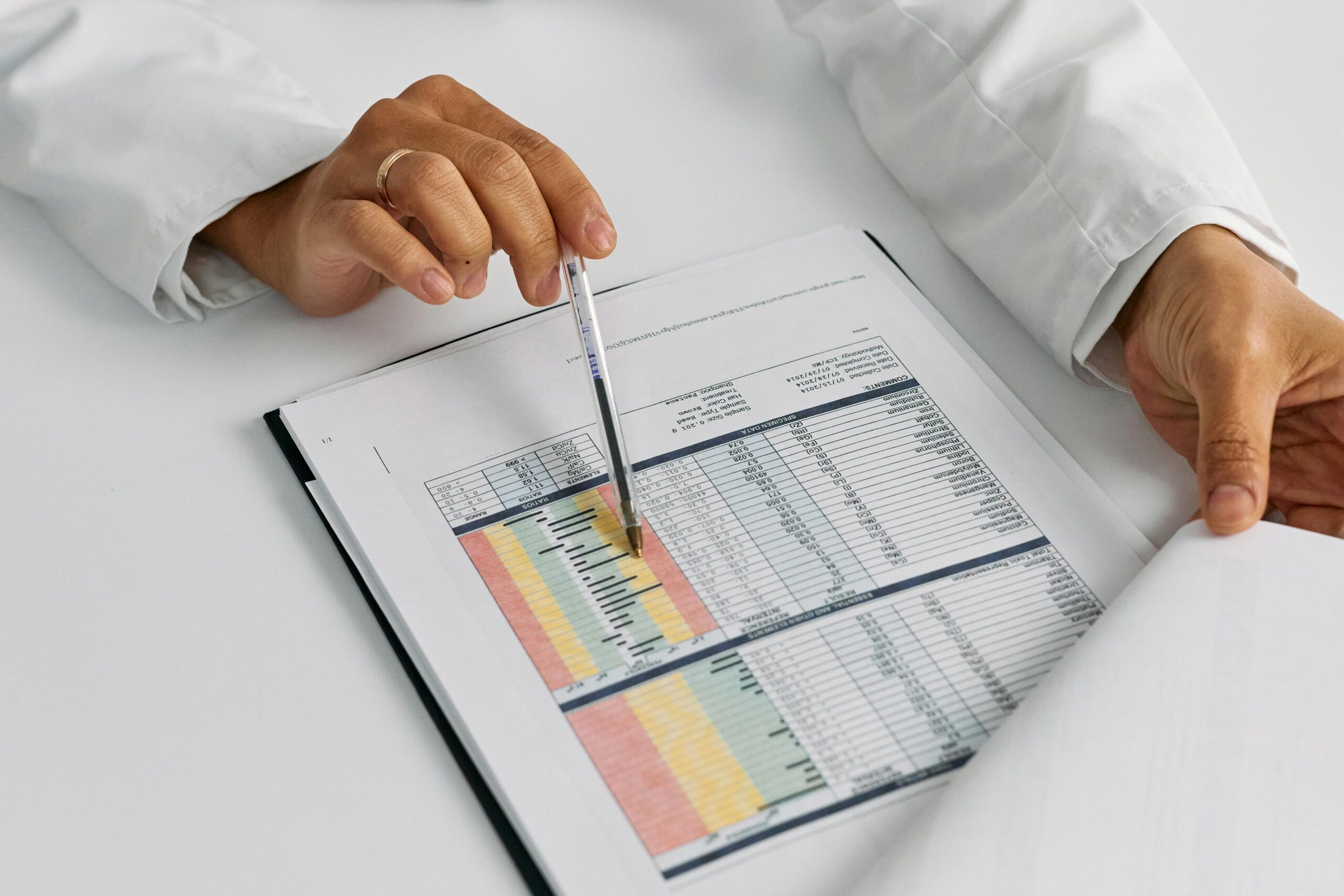

Blood tests for micronutrient status offer more objective assessment than dietary tracking, but interpretation requires nuance. Serum levels don’t always reflect tissue stores—magnesium exemplifies this disconnect, as less than 1% of body magnesium circulates in blood. Acute inflammation alters multiple micronutrient biomarkers regardless of true nutritional status. Reference ranges reflect population distributions rather than individual optimal levels.

Different measurement methods yield different results, and standardization across laboratories remains imperfect. Vitamin D testing particularly suffers from inter-laboratory variability. Seasonal variations, recent dietary intake, hydration status, and even time of day influence some biomarkers. A single measurement provides limited insight compared to trends over time, yet serial testing is expensive and often impractical.

When Testing Makes Sense

Despite limitations, targeted biomarker testing serves important purposes. Screening high-risk populations for specific deficiencies—vitamin B₁₂ in older adults, iron in menstruating women, vitamin D in individuals with limited sun exposure—identifies problems requiring intervention. Monitoring known deficiencies during treatment confirms that supplementation strategies are working. Investigating unexplained symptoms potentially attributable to micronutrient imbalances can reveal correctable causes.

Comprehensive micronutrient panels testing dozens of vitamins and minerals simultaneously generally provide more information than actionable insight. Focusing on micronutrients relevant to your specific risk factors, symptoms, and dietary patterns offers better value. Working with knowledgeable healthcare providers to interpret results in clinical context proves essential for meaningful application.

🎯 Practical Strategies for Navigating Uncertainty

Given the pervasive uncertainty in micronutrient research, how should you approach optimal nutrition? First, prioritize dietary diversity. Consuming varied foods from multiple categories—vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, and if appropriate for your diet, animal products—provides overlapping micronutrient sources that compensate for individual food variations and gaps in nutritional knowledge.

Focus on patterns rather than individual nutrients. Mediterranean, DASH, and traditional Okinawan diets all support health despite differing dramatically in specific micronutrient profiles. These patterns share common elements—emphasis on minimally processed foods, abundant plant foods, moderate portions—that appear more important than precise micronutrient ratios.

Strategic Supplementation

Consider supplementation for nutrients difficult to obtain adequately from food given your specific circumstances. Vitamin D during winter months in northern latitudes, vitamin B₁₂ for those avoiding animal products, and iodine for individuals not consuming iodized salt or sea vegetables represent evidence-based applications. Use supplementation to address specific inadequacies rather than attempting to optimize every micronutrient simultaneously.

When supplementing, avoid mega-doses unless specifically indicated for diagnosed deficiencies under medical supervision. More isn’t always better—and often is worse—for micronutrients. Moderate doses closer to dietary reference intakes minimize risks of imbalances and interactions while addressing potential inadequacies.

🔮 The Future of Personalized Micronutrient Guidance

Advances in metabolomics, proteomics, and systems biology promise more sophisticated understanding of individual micronutrient requirements. Wearable sensors may eventually provide real-time biomarker monitoring. Artificial intelligence might integrate genetic, dietary, biomarker, and health data to generate truly personalized recommendations. These technologies could transform micronutrient optimization from population-level guidelines to individually tailored strategies.

However, technological sophistication won’t eliminate fundamental uncertainties. Complex systems exhibit emergent properties that reductionist approaches cannot fully predict. Human biology’s adaptive capacity means that optimal nutrition may involve periodic variations rather than static targets. The social, cultural, and psychological dimensions of eating transcend purely biochemical optimization.

🌟 Embracing Imperfect Knowledge

Perfectionism about micronutrient intake can paradoxically harm health by creating stress, disordered eating patterns, and social isolation. Orthorexia—an unhealthy obsession with eating perfectly—represents a genuine risk when nutritional optimization becomes all-consuming. The stress of constantly worrying about micronutrient adequacy may outweigh benefits of modest nutritional improvements.

Accepting uncertainty doesn’t mean abandoning efforts toward better nutrition. Rather, it suggests balancing evidence-based dietary improvements with flexibility, pleasure, and sustainability. Incremental positive changes maintained over years produce better outcomes than perfect adherence to optimal protocols sustained briefly before inevitable abandonment.

The scientific method progresses through iterative refinement, accumulating evidence while acknowledging limitations. Nutritional science remains relatively young compared to physics or chemistry, operating within extraordinarily complex biological systems. Current uncertainties reflect this reality rather than fundamental failures. As research continues, recommendations will evolve—sometimes confirming current guidance, sometimes revising it substantially.

Your personal approach to micronutrient optimization should reflect your individual context—health status, dietary preferences, access to various foods, budget constraints, and priorities. What works for elite athletes differs from what suits sedentary office workers. Pregnancy, illness, aging, and environmental stresses all modify requirements. Generic advice, however well-intentioned, cannot fully capture your unique circumstances.

Building nutritional literacy—understanding fundamental principles rather than memorizing specific recommendations—equips you to critically evaluate new research, marketing claims, and dietary trends. Recognizing study limitations, industry influences, and the difference between correlation and causation helps you navigate the endless stream of contradictory nutritional information flooding media channels.

Ultimately, micronutrient optimization represents one component of health alongside sleep, physical activity, stress management, social connections, and psychological wellbeing. Obsessing over vitamin intake while neglecting these other domains produces suboptimal outcomes. Integrating reasonable attention to nutrition within a holistic approach to wellness offers the most promising path toward thriving health despite persistent scientific uncertainties. 🌈

Toni Santos is a soil researcher and environmental data specialist focusing on the study of carbon sequestration dynamics, agricultural nutrient systems, and the analytical frameworks embedded in regenerative soil science. Through an interdisciplinary and data-focused lens, Toni investigates how modern agriculture encodes stability, fertility, and precision into the soil environment — across farms, ecosystems, and sustainable landscapes. His work is grounded in a fascination with soils not only as substrates, but as carriers of nutrient information. From carbon-level tracking systems to nitrogen cycles and phosphate variability, Toni uncovers the analytical and diagnostic tools through which growers preserve their relationship with the soil nutrient balance. With a background in soil analytics and agronomic data science, Toni blends nutrient analysis with field research to reveal how soils are used to shape productivity, transmit fertility, and encode sustainable knowledge. As the creative mind behind bryndavos, Toni curates illustrated nutrient profiles, predictive soil studies, and analytical interpretations that revive the deep agronomic ties between carbon, micronutrients, and regenerative science. His work is a tribute to: The precision monitoring of Carbon-Level Tracking Systems The detailed analysis of Micro-Nutrient Profiling and Management The dynamic understanding of Nitrogen Cycle Mapping The predictive visualization of Phosphate Variability Models Whether you're a soil scientist, agronomic researcher, or curious steward of regenerative farm wisdom, Toni invites you to explore the hidden layers of nutrient knowledge — one sample, one metric, one cycle at a time.